CR 083: Christopher Eliopoulos on Cartooning, Comic Books, and the Fun of Drawing Princess Diana

The acclaimed illustrator discusses his career and his latest release, “I am Princess Diana.”

Social media is rarely associated with positivity and friendship, so it’s surprising that a hugely popular children’s book series that promotes kindness, compassion, and empathy might not exist if it weren’t for, of all places, Twitter.

It started when New York Times bestselling author Brad Meltzer and comic book illustrator Christopher Eliopoulos connected on the site. “[Brad] had started his show on the History Channel,” Eliopoulos says. “We were following each other on Twitter, and he started doing a viewing—you know, nights where they would view the show, and he’d tweet out what was happening. I would respond. I was a history buff from day one. I just love history. At one point [Brad and I] were going back and forth, and then he started sending me direct messages, as opposed to out in public.”

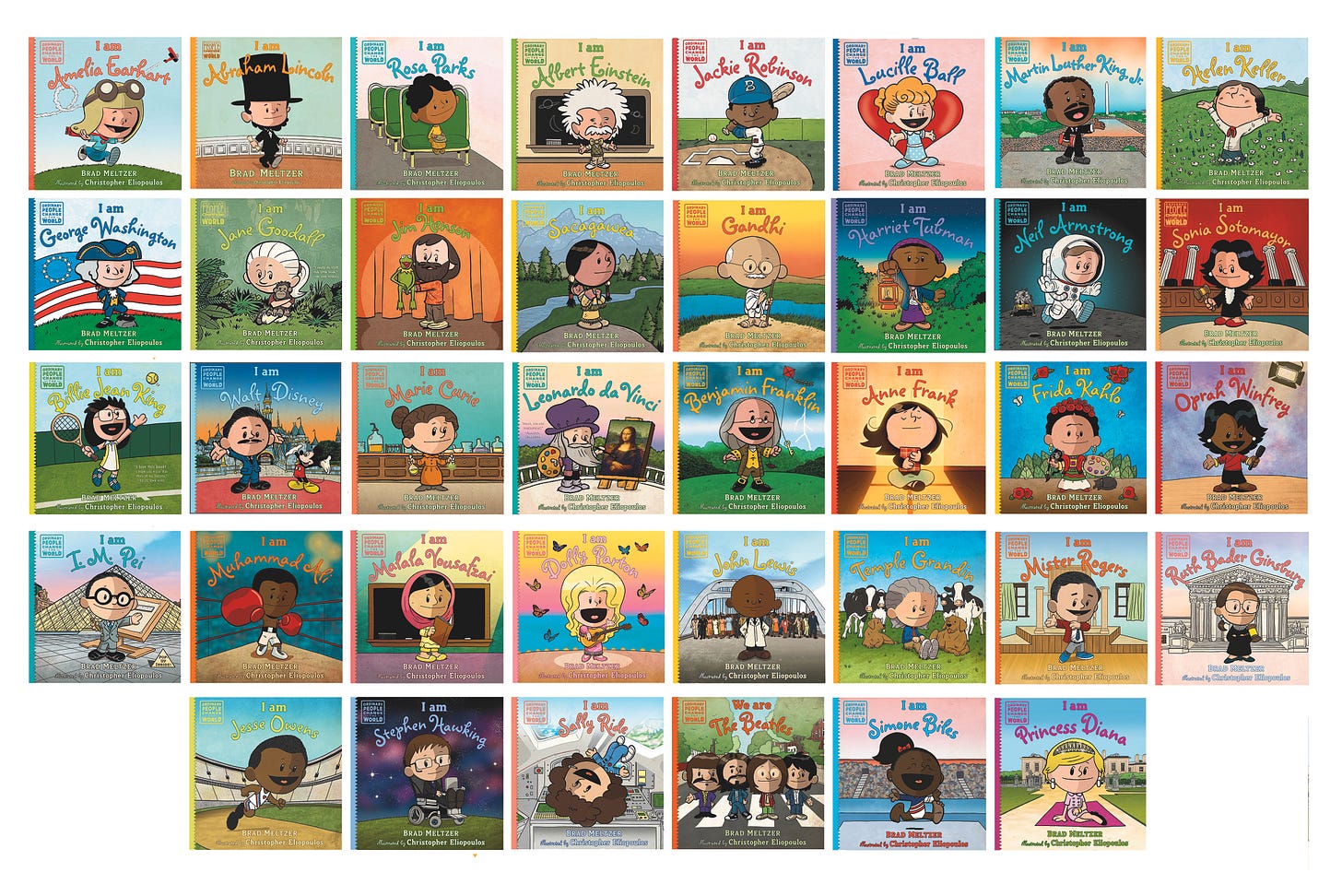

The two developed a friendship and soon began working together on a series of picture books called Ordinary People Change the World. Each release in the series—always starting with the title I am—tells the story of a notable historical figure and is drawn and lettered in a playful way to teach children about important character traits. But as Eliopoulos points out, adults can benefit from reading the books, too.

“I was at a comic convention soon after [I am Albert Einstein] came out. Now, comic book people are notoriously jaded, and this woman came up and asked me to sign the book. Normally when I sign it, I’ll write a little something and do a drawing of the character. I wrote, ‘Be weird,’ signed it, handed it back to her, and she started sobbing. I was like, ‘Oh my God! What did I do wrong? I’m so sorry.’ And she went on to explain that she and her husband are on the spectrum. Their son is autistic, and most people believe that Albert Einstein was on the spectrum somewhere. She’s like, ‘This book finally gave me license to say it’s okay to be different and weird.’ It hit her in that moment where she obviously had been struggling for years, struggling with her child, and it meant the world. So, I love that we’re affecting adults as much as we’re affecting kids.”

From his office in New Jersey, Eliopoulos chatted with me about his influences, his thoughts on the state of cartooning today, and the latest release in the Ordinary People series, I am Princess Diana.

This content contains affiliate links. I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

SANDRA EBEJER: I like to ask people how they got into the line of work they’re in. Thinking back to your childhood, were you always drawing? Was cartooning something you knew you wanted to do from a young age?

CHRISTOPHER ELIOPOULOS: I was an extremely short and extremely shy kid, and I was not very communicative verbally. I would not tell people how I was feeling or what was going on at school. My kindergarten would have the reading circle, and I would sit on the other side of the room. I just could not manage that whole thing. But there were a couple of things that helped. I remember drawing in kindergarten and my teacher said, “Oh, you’re an artist. You’re really good.” And there’s that moment in everyone’s life where somebody tells you you’re good at something, and it clicks. I even have report cards from that era, saying, “Chris is very artistic. He likes to write; he likes to draw.” But I was very shy and didn’t want to talk to anybody, even my parents.

One day I had a really bad day. Three girls had picked on me. They were merciless, and I was destroyed and couldn’t verbalize it. I couldn’t tell anybody how I was feeling. Held on to it, got all the way home, went up to my room, and for some reason, started drawing out as a cartoon what I was thinking and feeling. I had learned this process by reading Peanuts, the comic strip. I loved it. I saw emotions and feelings in there that I had. So I did the drawing, folded it up as a paper airplane, and mailed it down the steps. To this day, I don’t know why I did that, but I did. And my mother found the paper, picked it up and read it, and came up and talked to me. And so I started communicating a lot that way with my cartooning work. I found words and pictures together fit me right. I just kept doing it for years and years. It’s my only way of finding peace in the world.

That’s interesting. I know a lot of writers who use their writing as a way to figure out whatever problem they’re facing. I’ve never thought of it as being similar with illustration. Have you continued to use art as a way to work through something?

Yeah. But, you know, when you’re paid to draw, you have to draw what they tell you to draw. You lose that thing you had as a kid, which is sitting on the floor with a notebook and drawing just for yourself. So I started doing comic strips that I do for myself, and I explore all that nonsense that’s rattling around in my head. I’ve been working on one now for a while. I haven’t posted it anywhere. I haven’t put it up online. I do it more as a form of therapy and a way to explore all the issues that I’m dealing with, because sometimes it’s hard to verbalize them. So for me, this is a way to explore that, and I don’t have an editor telling me I can’t talk about this or I can’t draw that or whatever. Sometimes the best work you do is for yourself.

I was never a comic book reader, so I didn’t realize lettering was such a huge component of that world. You’ve done lettering for thousands of books, everything from kids’ books to adaptations of Stephen King’s works. How did you first get into that line of work?

I was in college. I wanted to be a cartoonist. My parents said I needed to get a degree in advertising and graphic design because I would never make a career out of cartooning. And one of the classes I had was with an old-time Marvel comics artist, Gene Colan, who took us to Marvel on a field trip just when I needed to get an internship. I figured Marvel is comics. I was more of a comic strip guy, but I figured it was adjacent to where I wanted to be and it might be the best way to get in the business. And my hero, Charles Schulz, started his career lettering comics. I said, “Well, if it’s good enough for Charles Schulz, I can do it.” They had seen I had typography, which I had taken in school, so they brought me in that way. In those days, it was lettered on the board. So on the actual artwork, you would take a crow quill pen, real ink, you would line up the pages with guidelines, and just letter in ink.

These days, it’s done all by computer. I’ve created a bunch of fonts. I actually don’t letter much anymore, except for my own work. I have a team of people who use my fonts and I oversee them, and they letter all of Marvel’s books. But for me, it was just a means to an end. I just wanted to get into cartooning and lettering was an entryway. And then, you get in good with people, you become friends with people in high places, and you say, “I want to be a cartoonist when I grow up,” and they give you opportunities. And so I was able to take that career in lettering and turn it into the career I really wanted.

Creative Reverberations is a reader-supported publication. Each interview takes many hours of work. To receive new posts and support my work, please subscribe.

I read that you first connected with Brad Meltzer on Twitter, and it makes me so happy to hear that something positive came out of that.

The one and only thing.

Yeah, right. How did you go from those early tweets to working together?

Well, it wasn’t that we didn’t know each other. In comics, it’s a very small community. You sort of know everybody. I knew of his work; he knew of my work. I sent him some of my work that I had done for Marvel, and other cartooning work. I was working on a pitch for a book and had gotten interest from a publisher, and he was the only published author that I knew in the business. I literally was texting him, “I need an agent. What do I do?” And my phone rings and it’s him saying, “Listen, I have this idea of taking historical figures and turning them into t-shirts.” We started to do these t-shirt things, and everybody was like, “Why are you doing t-shirts? You guys do books. Do books.” So he said, “Do you want to do a series of books with me?” And I’m like, “Yeah! I love history. I love cartooning. This will be great.”

He did a book called Heroes for my Son and one of the characters was Amelia Earheart, and he handed me the paragraph that he wrote and said, “Make this a children’s book.” I literally broke it down and drew up a bunch of pages. We went back and forth a bit and then shopped it around, and it was really that simple. What’s funny is we didn’t know each other that well. And then the week before we went out on tour for our first two books, we went on vacation together with our families. So, the best thing out of this book series has been this friendship I’ve had with Brad. And it all came from Twitter, God help us all.

Go figure. The first two books in the Ordinary People Change the World series were published in 2014. Was it a big transition to go from the comic book world into illustrating historical fiction for kids?

Yeah. With comics, you finish up a book and three weeks later it’s on the newsstand. It’s a work-for-hire situation. They pay you, and then they own everything you do. You go into the mainstream publishing and with Brad, because he’s so big in the industry, I entered the industry on the penthouse. We got everything, and I didn’t know it was any different. I was like, “This is amazing!” And then you talk to other friends who are like, “I don’t get that.” And it’s like, oh, okay, there’s a different stratosphere that I walked right into.

But also, to do a book and finish it and wait for a year to get a reaction is kind of insane. I always hear comedians talk about how they love doing stand-up versus TV shows or whatever because the gratification is instant. You can get a laugh right there on stage. And comics is very similar. You put something out, three weeks later, it’s out and you’re hearing about it. I forget what I’ve done a year later, and [the book] comes out and people go, “I love this. I saw you hid this person in the book.” And I go, “I did? I don’t remember.” So it really is a different world—agents and publishers and book tours. In comics, they don’t send you on book tours. But also, the fact that I own the artwork and I can turn to a publisher and say, “This is what I want. I’m not changing it” is a really nice thing to have. It’s a very creative way to go about it. Yes, sometimes Brad and I go back and forth, but for the most part, I get a say, which I never got in comics.

I remember when the I am Abraham Lincoln book came out. My son was a toddler at the time. I remember him sitting on my lap so I could read it to him, and then we got to the page depicting slaves in chains. I should have seen that coming, but it was jarring. So I’m curious, when you do books that address topics like slavery or the Holocaust, how do you balance the historical accuracy with the fact that this is a cartoonish thing that little kids might read?

That is the biggest issue that we deal with, because we don’t want to minimize the horrors of those events. You don’t want to make fun or light of it. And so it is tough. Like with Abraham Lincoln and Amelia Earhart, our first two books, they die horrible deaths. A reviewer of the Lincoln book said, “We didn’t get to see how they died.” And we were like, “This is for, like, eight-year-olds. Do you want a scene where he gets shot?” When we talked about the Anne Frank book, we were both a little bit tepid about it, but there was such a rise in antisemitism happening, we felt like we needed to point out that this is something that happened. It’s tough, but you can’t shy away from it. Kids have to know their history, right? Like the old saying, those who don’t know their history are doomed to repeat it, and we’re doing that even nowadays, in this climate. People are forgetting our history or dismissing it and saying, “You shouldn’t talk about this. You’ll make kids feel guilty.”

I see it as a point of looking at the good in people. We can change, like Lincoln changed his thought process. We looked at the Holocaust and said, “We’re not going to allow this to happen again.” It’s tough to sell, but I’m the sugar that helps Brad’s medicine go down. When kids like the artwork, and you tell them, “By the way, these are bad things that happened,” it’s easier to go down and they’re able to figure it out. All the books that we’ve done on civil rights and slavery and Harriet Tubman and Rosa Parks and MLK Jr.—they need to hear this stuff and sometimes it’ll be a little easier to digest with the cartooning.

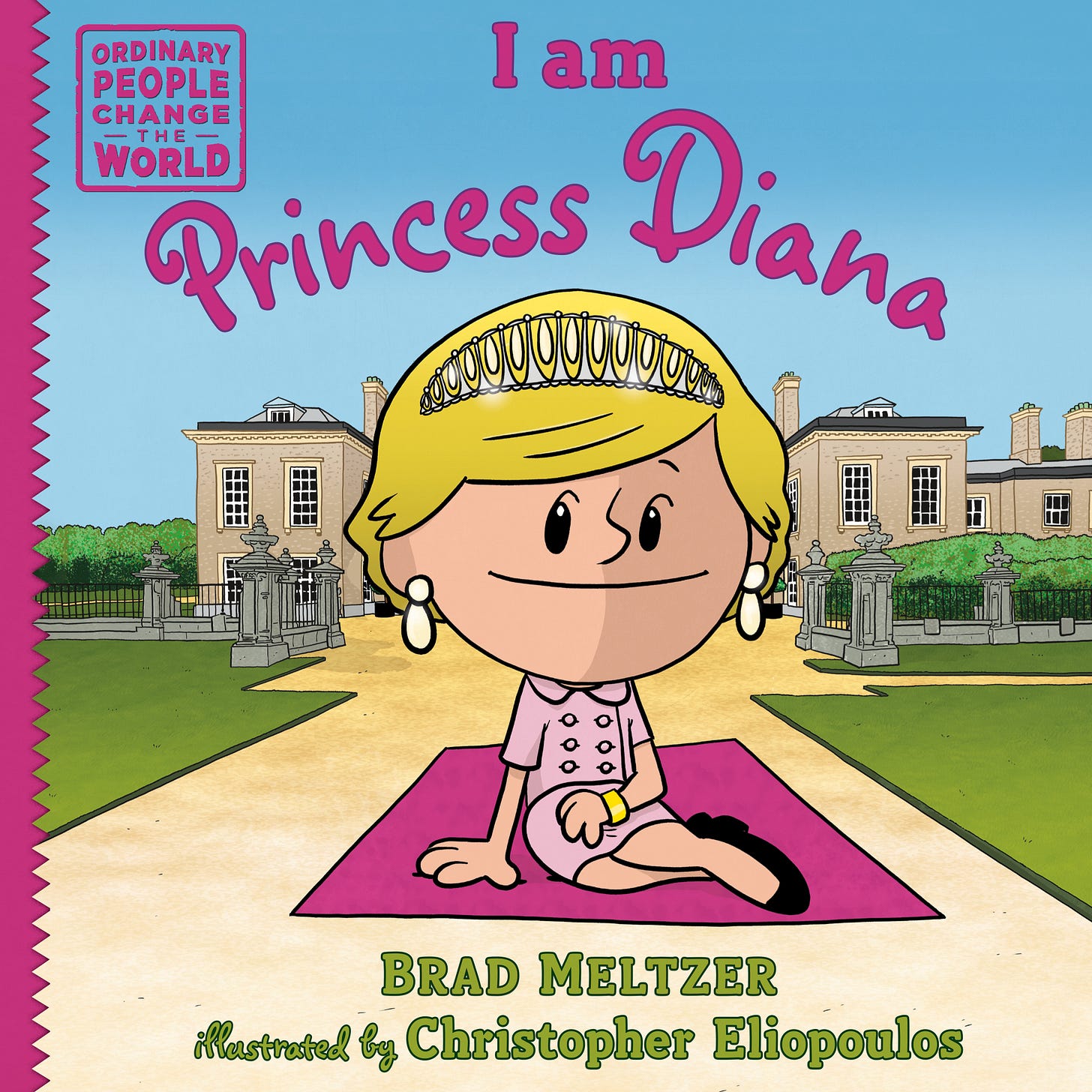

What can you share about the I am Princess Diana book that just came out?

We get together, Brad and I and our publisher, to figure out who we’re going to do next. And I remember a few years ago I said I’d really love to do Princess Diana, so she got on the list. We try to figure out what is the key to this person, what makes them important, especially right now. And we looked at what she had done and realized empathy was her gift. She brought empathy everywhere and these days, we seem to be lacking empathy. So it was fun to explore this person who was elevated to such a high rank and yet related to the least among us.

I just loved doing this book. It’s fun to draw her running around as a kid, which we do in all the books, but giving her a little tiara to run around in was fun. I fall in love with every character we do. Not love as in “I want to marry this person.” There’s a Greek word, agape. It’s like a love for all of humanity. She had that, and I related to that. And I have that with her, this universal love of who she was and what she stood for.

You mentioned Charles Schulz and your love of the Peanuts comic strip. I see a lot of Bill Waterson and Calvin and Hobbes in your work. Who are some of the other artists who either inspired or influenced you?

Schulz was the first and biggest influence. Watterson was after. Berkeley Breathed did a strip called Bloom County, which I loved. Crockett Johnson, of all people. He did Harold and the Purple Crayon, but he also did a strip called Barnaby. Very simplistic styling, but I loved his work. Walt Kelly, who did Pogo. I could go on and on and on. Back in the turn of the 20th century, George Herriman did a strip called Krazy Kat. Absolutely amazing work when you go back and look at it. He was so ahead of his time. He didn’t have a big audience, but he was such a brilliant artist. We finally caught up to him. So yeah, I like everything—Warner Bros. cartoons, Disney cartoons, you name it. I’ve pulled stuff in that you don’t readily see outright but have influenced me.

The days when you could get the Sunday paper and see page after page of comic strips are long gone. Is it still possible to build a career in comics?

It depends on the type of career you want. Newspapers are going away. The age of the millionaire cartoonist working in newspapers is over. There are so many kids—kids to me, anyway—who are doing great work online. They create their own website, they post it, they create a business. I have friends who literally do strips online. They sell product. They have patrons. Patreon is a great resource for them. I think anybody who needs to say something or tell something through their art will have a place. You may not be a bazillionaire, but I think you’ll make a good living.

You know, everybody always asks me, “What does it take to get where you are?” It was really just a love of the medium, doing it over everything else, having somebody that inspired you to do it, and somebody who encouraged you to keep going. I’ve had the luck of all of that. And I think anybody that’s willing to work for the love of it, the money will find you somehow.

You have a line in one of your Substack posts where you write, “Picture books may seem simple, but it’s a lot of work to make things look simple.” Are there any projects you’ve worked on that were particularly challenging? Anything that you felt really proud to have pulled off?

Every single one of them is difficult. Cartooning is all about taking everything and boiling it down to its simplest lines. You really want to bring it down to just the core. But it’s a nightmare. It’s easy to crosshatch something to death, but to find that one perfect line, whether it’s a drawing line or a writing line, is difficult. I still struggle with it every single day.

The first picture book that I wrote and drew was called The Yawns are Coming. It was the weirdest thing. I wanted to do my own books. I was struggling like crazy for an idea. I was getting my hair cut. I was yawning. I was tired, probably from staying up trying to come up with an idea and bashing my head against the wall, and I started yawning. I said, “Oh, the yawns are coming.” And for some reason, it triggered a thought in my head that the yawns are like these little creatures that force your mouth open to make you yawn. And literally, I came home and wrote out the whole book in an hour. Pitched it. They loved it. Did it, and it came out right on lockdown. Literally, all the bookstores closed, everything, the week of. Luckily, later on, it got pushed into an Amazon box thing and sales took off, which is great, because I just wanted people to read it. But I was really happy with the way it all just flowed. The story itself, where I went with it, where it ended up, was just a joy, and I’ve been trying to recapture that every single time, to varying degrees of success.

You’ve done so many incredible projects in your career. Is there anything you haven’t done yet that you’d like to do?

I’d love to do a movie at some point. I never thought any of this was possible, so the idea of a movie would be fun to put together. Maybe my own show, separate from Xavier Riddle. I love [my show with Brad Meltzer] Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum. It’s on PBS Kids. Now that the government has pulled funding from PBS Kids, that old saying, “PBS is brought to you by viewers like you”—now more than ever, they need that support. So if you ever come home with a few extra dollars in your bank account, if you would donate, I think they do amazing work. I grew up on Sesame Street and Mister Rogers and Electric Company, and we need to keep them going.

And I just want to keep drawing. Everybody goes, “You must have an exciting life.” It’s the best. I sit in a room alone drawing all day. I do the thing I did as a kid that I loved to do, and nothing has changed. I love doing this. As long as I can stay here and draw, I’m happy. I’m working on an autobiography right now that I’m hoping will come out soon, so you’ll get all the stories through pictures and words. But, I mean, if you asked 10-year-old me what I would do more than anything, it’s to sit in my room drawing pictures, and I get to do it. So who’s better than me?

To learn more about Christopher Eliopoulos, visit his website.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You might also enjoy…