CR 062: Dar Williams: ‘I love that I’m part of this group that is keeping it weird and diverse out there’

The acclaimed singer-songwriter and author discusses her new album, “Hummingbird Highway.”

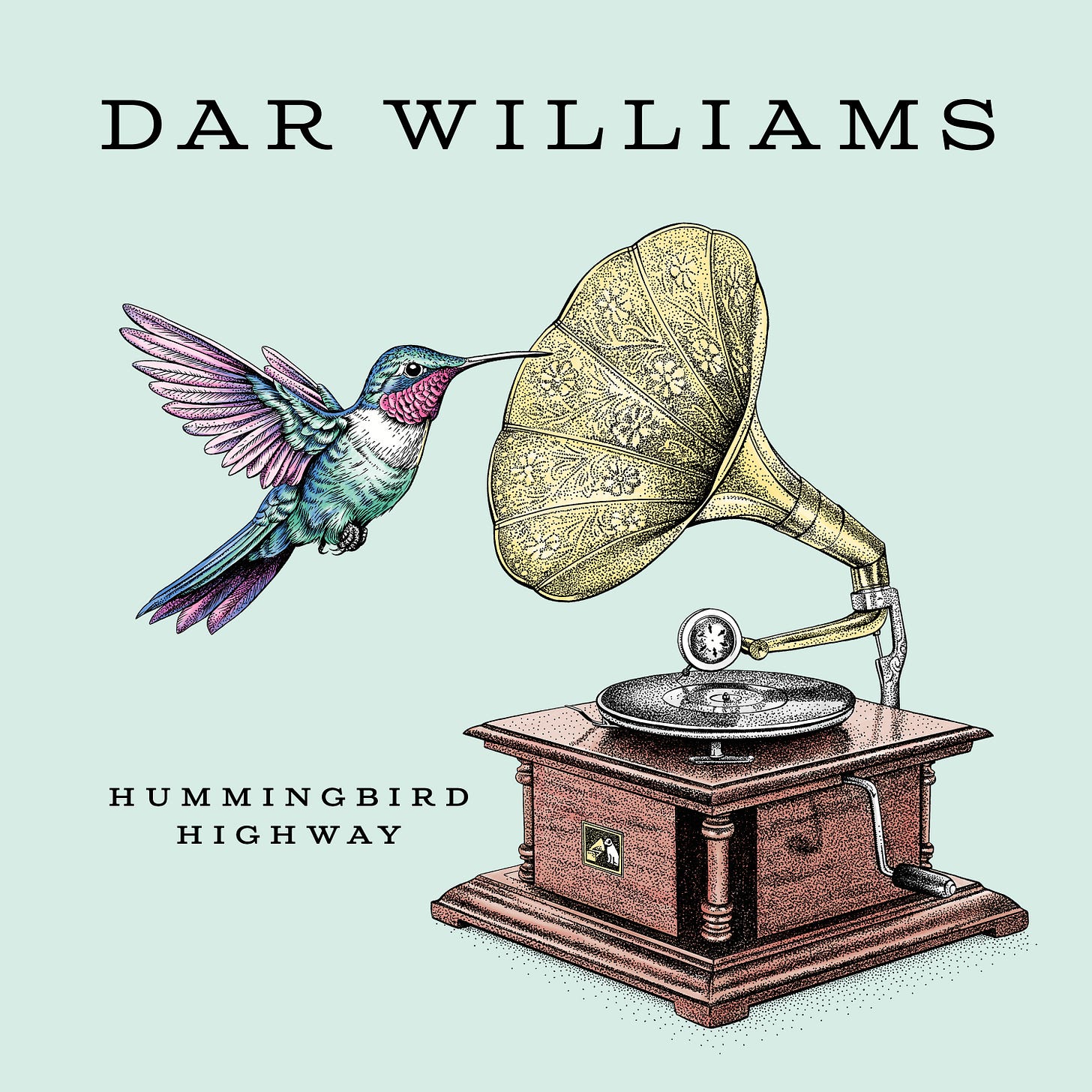

Dar Williams has been referred to as “one of America’s very best singer-songwriters” (The New Yorker), with “a playwright’s sense of narrative” (The New York Times) who sings “with full attractiveness” (Americana Highways). Over the course of 12 albums spanning 35 years, Williams has addressed an array of topics—among them, ageism, politics, religion, body image, and gender roles—with thoughtfulness, humor, and wit. Today, she’s releasing her 13th album, Hummingbird Highway—her first on Ani DiFranco’s indie label, Righteous Babe Records. And though the single “Hummingbird Highway” has already received praise for its gorgeous reflections on the challenges of parenting as a touring musician, Williams admits it wasn’t her first choice as an album title.

“I was thinking of calling the album Civilization,” she says. “Because it bops around time and space, and how we try to civilize ourselves. And my manager was like, ‘You’re kidding, right?’ [Laughs] She’s like, ‘So we have a really boring t-shirt with a geometric pattern on it? No thank you.’”

Over an hour-long phone call, Williams—who is incredibly down-to-earth, hilariously self-deprecating, and quick to laugh—talked about her transition from aspiring playwright to songwriter, her musical influences, and what she’d like to attempt next in her career.

This content contains affiliate links. I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

SANDRA EBEJER: I want to start out by talking about your background. I read that you had planned on being a playwright. How did that transition to a career in music?

DAR WILLIAMS: It was a huge help. I was really lucky because I went to a school where being a drama major meant that you could direct a play in a closet and they’d give you a budget. [Laughs] It was when there were so many different experimental things going on. You could do a play with no words; the emphasis was on how you told a story. And so it was actually kind of an easy transition. When I got to Boston, there wasn’t a lot of local theater. Most of it came out of New York. But you could go to an open mic seven days a week, literally. You had to search around, because some of them were like once a month, and they were called the new moon, the crescent moon, the half-moon, the full moon. But it was very accessible, and again, all over the map. People ranted, people did poetry, and people sang long, endless songs. I felt like I could fit right in. It was storytelling with new tools, where instead of costumes and dialogue, you had music and rhythm and performance itself. I mean, I was terrible, but it was like my $100 grad school. You go to 50 open mics and pay $2 to sing, and you even get a free brownie. [Laughs]

Your songs are so full of rich imagery and characters. When writing a song, do you tend to start with the lyrics? Or is it the melody that drives it?

I used to say it went song to song. But I’ve come to realize that the music drives what I call the voice of the song. I was trying to come up with a helpfully vague thing of what you experience when you know you’re on to something with a song, and you can figure out the path. I call it the voice. So for me, the music is what helps me understand what the voice of the song will be. And then I plug in the things that are interesting to me.

The other day, I came up with all these pretty chords, and I just didn’t have a lot of pretty things that I wanted to write about, so I found this really dissonant chord, and I thought, “Oh, there we are.” Usually what will happen is I will find something that sounds interesting, and I will go through the whole gamut of emotions and things that are speaking to me in the moment. I found myself singing, “Where is my rival?” I remembered I’ve had so many rivals who, on the other side of many years, come back and we describe our battles together. We’re very close friends now, and we love each other. It’s an incredible way to know who you are. And of course, rival is a beautiful word, so there might be something emerging out of the fog there. And so maybe I’ll keep the pretty chords. But it’s music. Definitely, for me, it’s music.

The new album is fantastic. Its title, Hummingbird Highway, is such an apt description of this frenetic world we’re living in. How did the title song come about?

I had all these little fragments, and I hadn’t put them together for a long time. This was in 2019, I think, and I was a performer on a Cayamo cruise, and my manager and I went on a day trip in Belize. And on the way down to this spice farm, which was so cool, they said, “We have three highways. We have a North highway, a South highway, and then the middle highway. It’s called the Hummingbird Highway.” And so it was everything about my life. There were many stories, all of which appeared in the song, like the beauty of my traveling career and the freneticness. There was a moment when my kids were like, “You know, when you bring us stuff from your trips to let us know you were thinking of us, it just reminds us that you’ve been absent and having this fantastic time.” There was a lot of, “Mom just got in from Cincinnati and is a little rough as she’s walking you to school this morning.” So the phenomenon of being a really busy parent with kids, the beauty of your life, and trying to share that was there right away.

I’m very defensive about the fact that, actually, when you add it up, I’m home more hours than commuting parents. And I love my job, and sometimes I take my kids with me. The truth is, when you bring your kids along with you or make them part of your creative career, it’s the best or worst of things. Ideally, you’re showing them really interesting stuff. But it’s disrupted routines, it’s confusion, it’s bad food. Anyway, that was in there right away. And when I was done with the song, this woman named Deb had this tattoo of a hummingbird. And I said, “Oh, you have a hummingbird.” She said, “My daughter has one, too. Hummingbirds fly in all directions.” Which is true. If you watch them, they go up and down, backwards, forwards. She said, “This is our way of reminding each other that we will find a way to find one another.” And I just thought, wow. That’s the whole song. That’s so cool. [Laughs] I had this really Gestalt [thought], like the incredible beauty of the living world, living with it, and then trying to be civilized in it, especially for our kids.

I’d love to talk about the third track on the album, which has a French title that I’ll butcher if I try to pronounce.

My answer is, “It’s the French song.”

Yes. I’ll call it “the French song.” It immediately jumped out because it has such a lighter, jazzier sound to it than the other tracks on the album. What was the inspiration behind that song?

It started all in French, and then I was like, “Yeah, check yourself, lady. There’s only so far high school French can take you.” [Laughs] But I had a picture in my mind of this spring evoking a certain kind of hopefulness and romance in this narrator, who’s [like], “Oh, dear. My dress just slipped off my shoulder. Excuse me, I lost a button on my shirt.” You know, the song “Iowa” [from 1996] is about Iowa being an evocative landscape for a narrator. I love those things where it’s like the world around us pulls us out of ourselves and brings us to this other place. And so, again, as soon as I had this melody and these characters, it was light and it was unmistakably bossa nova. And there was so much hitting the fan politically at that moment. It was a couple years ago. I brought it to my friend’s house, and Beth Nielsen Chapman was there and some of my co-leaders of the songwriting [retreats], and they said, “Keep on going. That sounds great.” And we started to flesh out the idea of the moon having the blush of a rose, and how great that is because rose rhymes with so many things. [Laughs]

So when I finally made it a hybrid of French and English, and I had the line “tu sais le printemps,” which means “you know the spring,” I mean, what a rationalization. I love the idea of, “Oh, sorry I hit on you. Well, you know, the spring. Oh, I just touched your hand. But, you know, the spring. We’ve been acrimoniously parted for 10 years, but [sigh] that’s spring.” And there was this moment where it says, “And of maddening times / we will laugh and say, That’s how it goes.” I thought, “That’s really true.” Again, I’m friends with people with whom I had so many love-hate moments and what it brought out of me was arguably something I don’t even want to remember, but that’s the way it goes, and we can laugh about it now.

This is your first release on Righteous Babe Records. I know you’ve known Ani DiFranco for many years. What made you decide to release this album on her label?

I was with a label called Renew that kind of hit the pause button right after we released the album [2021’s I’ll Meet You Here]. They did a beautiful job, but it was time to find another thing. And there’s some lovely businesses out there, but it really does have to— I don’t really understand how this thing called the 360 works. Have you heard of this 360 contract?

No. I’m not familiar with it.

Basically, you sign up with people in a 360. They get a percentage of everything that you do, and they’re incentivized to find commercial uses for your music. The best example of that is Katy Perry dressed as a Flamin’ Hot Cheeto for Halloween and saying it’s just because she loves them so much. Which might be the case, but she’s also got a really huge endorsement with Pepsi. It’s the corporate Medicis. You either can get into that world, or it’s got to feel like family. And there are some really beautiful labels out there that feel like family. I can name about seven or eight of them. [Sighs] But...Ani. [Laughs]

So we reached out to Righteous Babe. We know a lot of people on the roster. Anaïs [Mitchell] and I are friends, and Peter Mulvey is a friend. She has this great outfit around her. She’s got great management and then the label itself, and there’s a lot of good spill between the two. I wanted to make sure it wasn’t me going to Ani and saying, “What do you think?” Because there’s many reasons to work together, but there are also reasons it might not work. I didn’t want to put her in that position. So, my people went to her people. Her people are the best. And I have to say, to have that pre-vetting of people, where I feel like someone’s looking at me and saying, “Oh, another human. We’re going to figure out how to help this artistic human do her thing” is really important. I’m fine at softening edges and finding ways to communicate with people who have mommy issues—this label has no mommy issues. I feel this incredible respect. They sent me flowers and said, “Welcome to the Righteous Babe family.” Some people do that in a really scary way [laughs], but this was real.

One of Ani’s colleagues described how her concerts create sanctuary for people who have been targeted by this administration. There’s a lot of gender fluidity in both our audiences, and so I love this idea that I’m part of this group that is keeping it weird and diverse out there. There’s a huge range of expression within the artists on that label, so it’s a bigger comfort to my heart than I expected.

Speaking of Ani, a few years back I interviewed her for a column where the interview subject was asked to put together a music playlist on a theme of their choosing. Her playlist was “My Friends on the Folk Circuit,” and she included your song “When I Was a Boy.” And she said, “This is the type of Dar Williams song that just slays me and inspires me to work harder as a songwriter.” I’m curious, who are your inspirations? Are there any artists that influence your work?

Okay, so Ani’s song “Fuel” and the breadth of what it takes on and how it has this incredible access—it’s such a deep, poetic landscape that she walks. When we walk to the store, we’re going from point A to point B. But when we’re walking to the store metaphorically, in the poetic landscape, that’s a way different terrain. And the richness of that poetic landscape was like permission. Some things give me permission, and they’re beautiful and they slay me. I mean, the bedrock for me has been between Paul Simon and Joni Mitchell. I call Joni Mitchell the—I can’t remember anymore. Is it Mahler? There was this person who introduced the chromatic scale to classical music, and somebody said it was Mahler, but I don’t think that’s right. But anyways, I have called her the Mahler of folk music, in terms of the color palette and the musical palette of what she brought to folk music. The song “Blue”—all of the chromatic scale that she uses in that is a good reminder to keep on finding the richer palette. That’s been really important for me.

I also love John Prine. Anytime somebody has said, “I don’t play guitar well enough to tell my story.” I’m like, “John Prine had songs that were four chords, tops, and told stories like ‘Sam Stone.’” And I think what I loved about Paul Simon and Simon & Garfunkel was they were from Long Island, and I grew up in the suburbs of New York and there’s this way that you can mythologize New York or urban places. There’s a longing and a kind of iconography [in] the song “The Sound of Silence.” David Byrne, too. I saw American Utopia, and there’s this way of claiming the world of ordinary things, like toasters and shoes and buildings, and giving them this poetic life. Ani [is] like that—sitting down in the middle of this rich poetic world and staying there and finding all of these meanings beyond just this geometric A to B walk. I had a friend. She was a Buddhist Republican. She’s like, “That would be a single bumper sticker. That bumper sticker would have one run.” [Laughs] But she said, “When we stop seeing the world politically, we’re done.” And I think that Ani, David Byrne, Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, John Prine, they kept everything awake.

And as I get older, it’s easier for me to experience that, but it’s harder for me to access what I call the silver key, which is that thing that opens the big file cabinet of songs. On a regular basis, I think I see the world in a more poetic way, but it’s harder to find the way into single songs that express what I experience.

That’s interesting. You’d think as you get older and the more you do this, the easier it would get. Why do you think that it’s harder to access that?

I think because it’s more of a permeated experience, and also maybe because you’re not fighting for it. You’re just appreciating it. I experience the spirit of being, and spirit of doing is ambition. It’s doing things, accomplishing things, proving yourself, and proving yourself to yourself. There’s a lot of birds on this album, which cracks me up, because a lot of the pandemic, while people were writing operas and ballets, I was just staring at the bird feeder. I couldn’t believe how incredible birds are. I was just really being during that time. And as you fall in love with being, it’s good to keep on doing. I go to a lot of museums, to remind myself of how people turn being into the creation of these art pieces. I feel like I’m surrounded by artists who are like, “Yeah, this is what we do. We try to spin this into gold.” There’s other more mechanical reasons why it might be harder to sit down and write a song, but that’s boring.

You’ve written hundreds of songs. You’ve written books. You’ve taught others how to write songs. You’ve toured the world. Is there anything you haven’t yet done professionally that you’d like to attempt?

Piano. I remember when I was pregnant and I was 37, I said, “I feel like it’s too late to learn.” And Patty Griffin was like, “Never too late. Always a great idea.” Of course, she plays like a virtuoso now. So, yes, there’s always something.

I wrote a teen novel for Scholastic. They invited me. They’re like, “We’re the Harry Potter people. We’re kind of flush right now. Would you like to write a book?” I was like, “I don’t know...” And my friends were like, “If they invite you to lunch, you go to lunch with Scholastic!” By the end of the meeting, I was like, “I have an idea.” So I’m working on a teen novel now. I’m kind of in love with the characters. I don’t know if I’m doing them justice, but that’s the big question. I would love to just keep on being interested. It was great to write the songwriting book, and I also wrote an urban planning book.

There’s not a lot of stones unturned, because I’ve always worked with people who really give me permission to follow a lot of weird muses, and one of them was my urban planning book, which opened the doors of perception. It changed my life to take that little lateral step. Anyway, the answer is, there’s always a new frontier. It used to be Spanish. I’ve been taking Spanish for three years, but now it’s like, “Come on, Dar, piano.” And maybe painting, which I would be horrible at. But who cares? I mean, you should see me doing Afro-Haitian dance. I love it. Don’t watch me, but I love it. [Laughs]

Well, you’re an amazing songwriter, so if you were great at everything, we’d all just hate you.

Oh, you’re so sweet. I’m a terrible landscaper. Not a great cook. But, you know, maybe if I were a great cook, I wouldn’t be as interested in traveling. Because a lot of this career is about being able to eat potato chips for dinner.

I do that, and I’m not a musician.

Exactly! It’s just about living, right?

To learn more about Dar Williams, visit her website.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You might also enjoy…