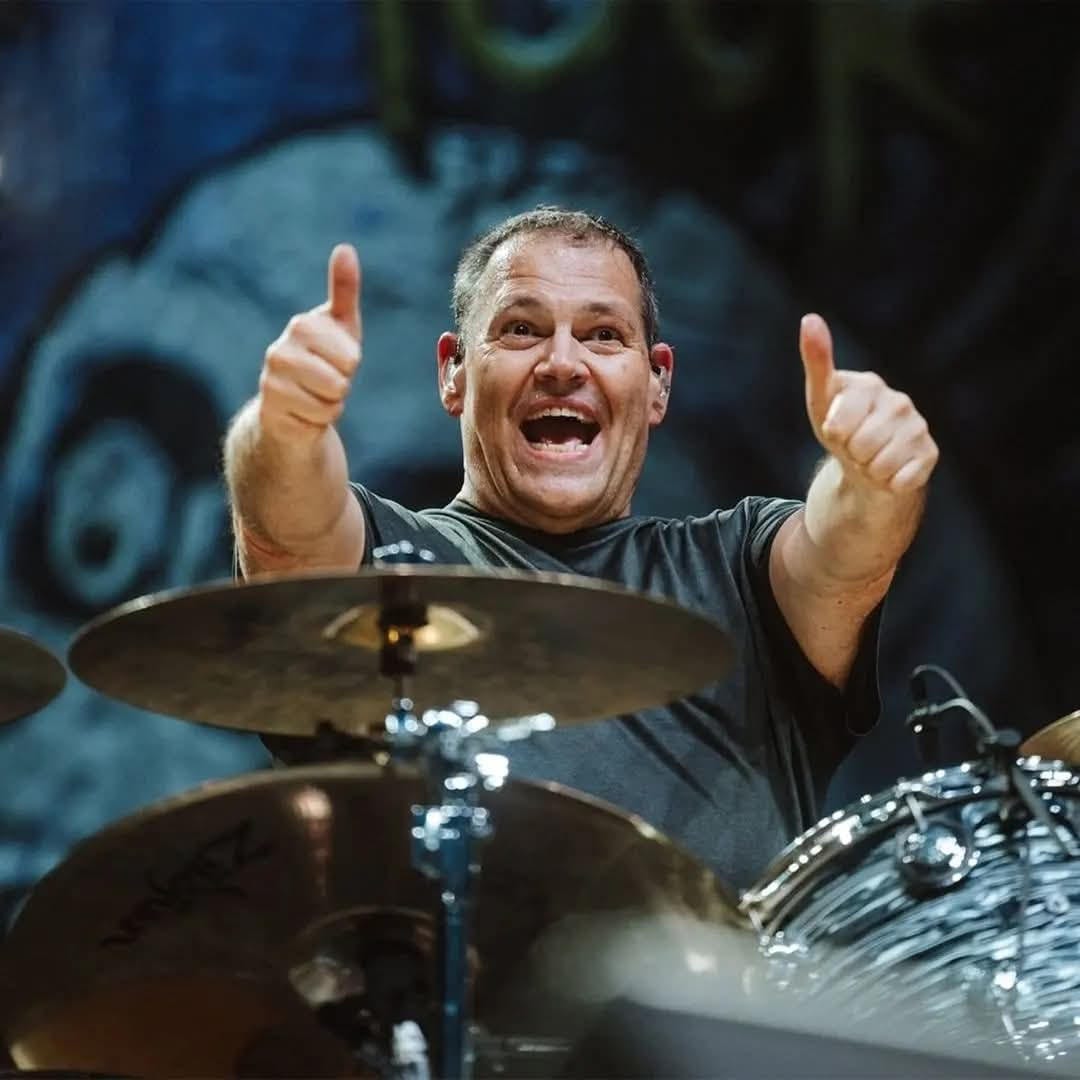

CR 071: Iconic Drummer Bill Stevenson on Punk Rock, Longevity, and Playing Music for Music’s Sake

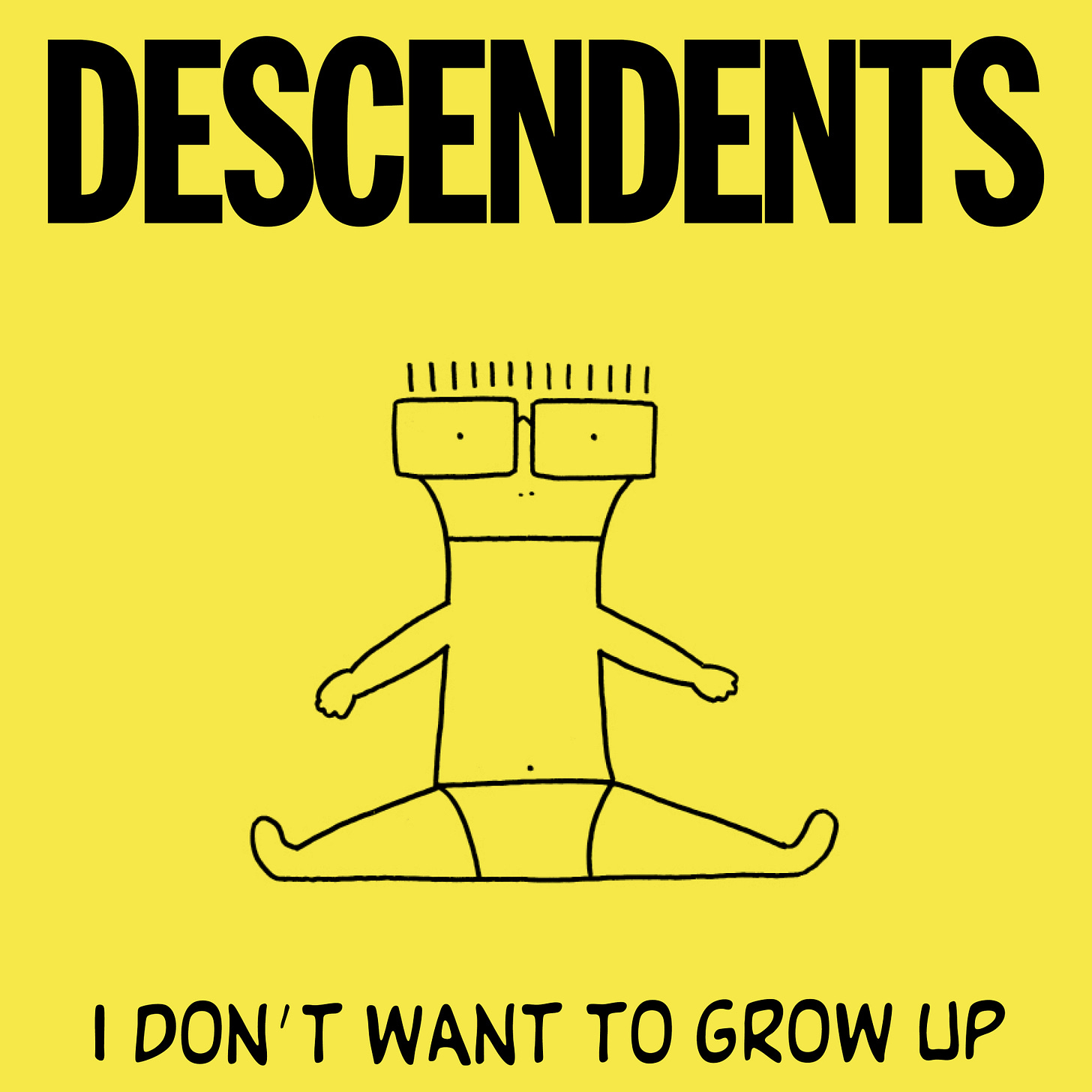

The legendary musician discusses the reissue of the Descendents’ “I Don’t Want to Grow Up.”

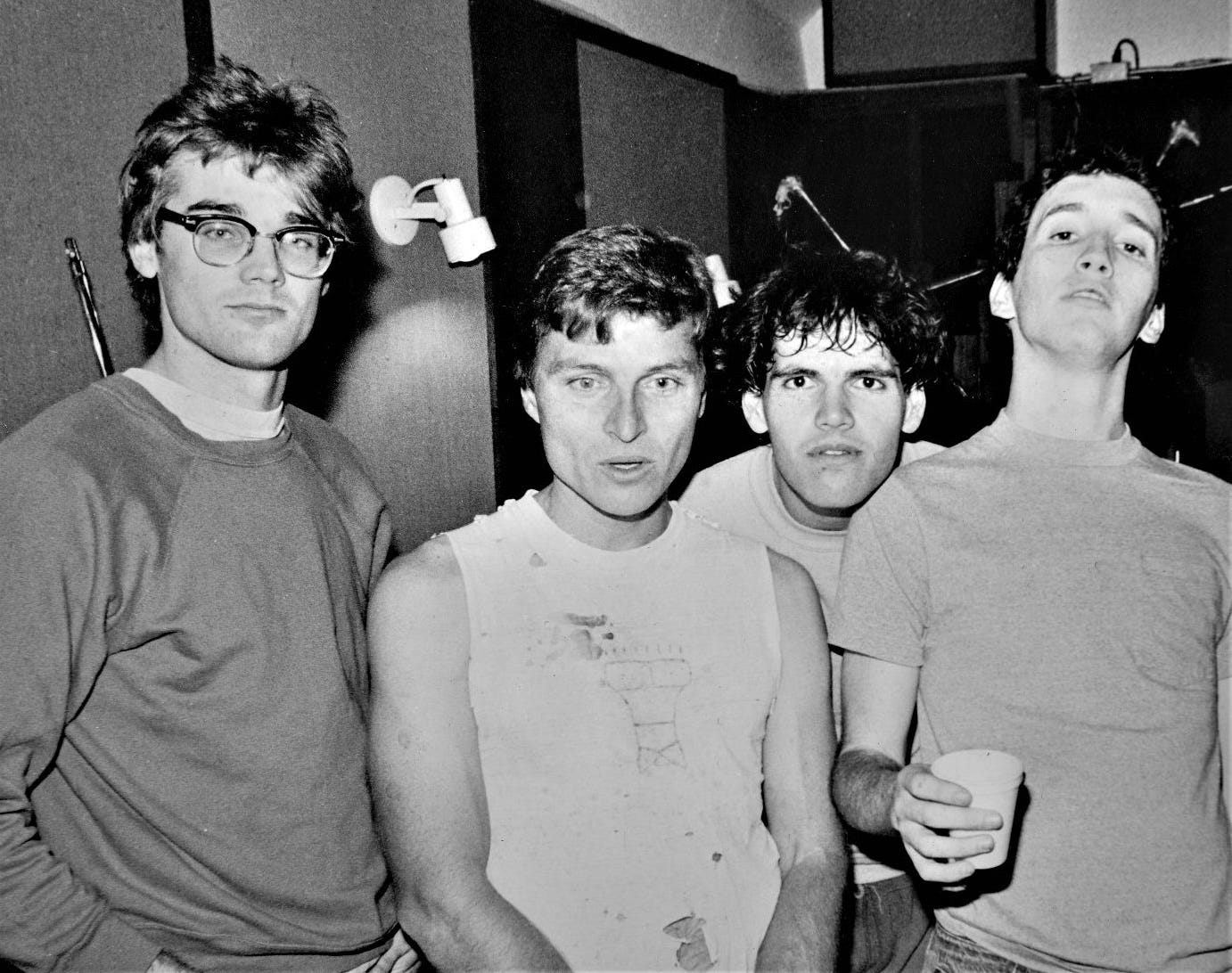

Bill Stevenson was just 15 years old when he and a couple of friends formed the Descendents, a band that melded punk, pop, surf rock, new wave, and coffee-fueled youthful energy to create a sound all its own. Despite its members having little musical experience and no master plan for success, the Descendents has gone on to become one of the most influential voices in rock music.

Stevenson, the band’s drummer and sole consistent member, has been name checked by numerous artists, including Dave Grohl and Josh Freese, as an inspiration and influence on their work. In addition to his drumming with the Descendents and its offshoot band, ALL, Stevenson served for a time as the drummer for Black Flag and the Lemonheads, and regularly produces albums for other artists at his Colorado studio, The Blasting Room.

Today, the Descendents is still going strong, performing regularly and working on new songs. On November 21st, Org Music will reissue the band’s second album, 1985’s I Don’t Want to Grow Up, on LP, CD, and cassette. And after nearly 50 years of hard work, Stevenson could not be more content.

“Because we never had a hit on the radio and there was no trendiness to Descendents, we never had a fall from grace or any kind of sophomore jinx to speak of,” he says. “We’ve just been chugging along. And in so chugging, we’re at the height of our popularity right now because it’s just been a steady chug uphill. We’re enjoying the fruits of our labor. So, it’s great. We’re family. When I’m on my deathbed, who the hell’s going to be in that room? It’s going to be my family and my band guys.”

Over a recent Zoom call, Stevenson discussed the early days of the band, his musical influences, and why touring is more fun now than ever.

Creative Reverberations is a reader-supported publication. Each interview takes many hours of work. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

SANDRA EBEJER: If the internet is to be believed, you’re 62.

BILL STEVENSON: Well, come on, you can’t believe the internet. I’m only 33. [Laughs] Yes, I am 62.

You founded the Descendents when you were a teenager. So many bands have come and gone during that time. What do you attribute to the band’s longevity?

We started it when we were 15. Tony [Lombardo, bass player] was several years older than us, but Frank [Navetta, guitarist] and I were 15. I think if bands start for the right reasons, they stay together longer. We started with no aspirations other than music for music’s sake. We’ve found ourselves in the punk rock scene, even though I don’t know that we’re a punk band in the orthodox sense of it. But in that scene, there wasn’t really the likelihood, or even the possibility, that your band was going to get famous or that your band was going to get popular or rich. None of that was really on the table. It was just strictly us doing it for the fun of it.

And also, it provided me with a friend group and a camaraderie the likes of which I had never experienced. So I hold it dearly, and I think I speak for all the guys with respect to that sentiment. Maybe along the way, in all those years, we had a few missteps where we would drift over a little bit [into the] poppy direction, which was unbefitting of us, but there were never any unsuitable motives. We just had the best time in our little garage practicing. And it’s still that way, really. My fondest memories of the band are all in a tiny, poorly ventilated practice room. I’ll love that as long as I’m able to play. I think the guys all feel that way, as long as we’re able to play and play proudly. You know, you see old bands and they suck live—when we start to suck live, we’ll probably bail. We don’t want to embarrass our legacy. But we’re doing really well now. We practice all the time. And in 2024, we played 92 shows. So, yeah, it’s going well.

When did you start playing drums?

I started playing not very long before the band started. In my freshman year of high school, my dad bought me a snare drum. It had this funny little $3 cymbal, like a vaudeville cymbal or something, and I played that for a while. I drove everyone crazy beating with spatulas on pots and pans or beating on my notebook with pens. The high school marching band was next to a couple of my classes, and I could hear them in the distance. They’re doing all those military beats, and those are easy to follow along, even if you aren’t a musical expert. And I would just always be pounding on something. So, I talked my dad into getting me a snare drum, and maybe I had that snare drum for six months, and then I got a drum set. And then maybe I had that drum set for another six months, and then we started the band. So I barely knew how to play when we started.

Who were your influences back when you guys were starting out? Were there any bands or musicians that you wanted to emulate?

My short answer to that is a recipe. If you want the Descendents recipe, it’s one-third The Last, a band from the South Bay—Redondo and Hermosa Beach. But they were before us, so they were kind of pre-punk. People called them a power pop band at the time. And then one-third another band that nobody really knows called The Alley Cats, and they’re another South Bay punk band that never really got their due. But if you look at L.A. flyers from ‘77, ‘78, ‘79, ‘80, you’ll always see The Alley Cats as the headliner, and then you’ll see other punk bands playing underneath them. And then the final third would be early Black Flag stuff, which we were all really big fans of. So that’s the short answer for what the influences were.

Then broader, growing up in L.A. in the late ‘70s—what was going on in L.A., to me, seemed like magic. It was just incredible. It changed my life forever, and it’s almost like it was a dream, like it didn’t really happen. We’d go to shows and you’d pay five bucks or whatever, and you might see on one show the Go-Go’s, the Germs, the Weirdos, and Fear. And there weren’t a lot of people at them, either. The people that showed up for that kind of stuff were people that didn’t fit in other places, people that were bored with where mainstream rock had ended up. When it got into these lightweight, prog-type sounding things—Styx, Supertramp, Kansas—a lot of people weren’t into that, and they had nowhere to go. It was like we had our own little world, and everybody in there were artists or people that were different in some way. It was great. It was a magical time to be a teenager.

That’s very cool. The reissue of I Don’t Want to Grow Up comes out later this month. What comes to mind when you think about the making of that album?

One thing that makes it different than all the rest is that we weren’t really active as a band. We were on a bit of a hiatus because Milo [Aukerman, lead singer] was down in San Diego going to school, and I was doing a lot of touring with Black Flag. It’s one of the only periods in my life when I didn’t have a practice room. There were like three months where we didn’t have a practice room, and that’s when we recorded I Don’t Want to Grow Up. We practiced it in a living room with the guitars not plugged in and me just tapping on a notebook. That’s how we practiced the songs, just in the living room, singing it unplugged. We practiced them unplugged because we didn’t have anywhere to practice them plugged. Between that and the engineer we used, David Tarling, and also just the tone of the times, there’s a lot of bizarre choices with the sounds on that record. It has a soft sound in certain ways, and it’s got that telltale, gated reverb on the snare drum, like hair metal. That’s how people were making records then and we were too stupid to change it. So those would be the things that stick out about it.

It was an intense time for me because I was in the process of leaving Black Flag and deciding that I wanted to get the Descendents into a position where they could be a touring band. We were never able to be a touring band because our bass player, Tony, was a full-time mailman. The most he could ever get off would be two weeks per year, so we were never able to tour. And when I left Black Flag, I said, “I want to go on tour. I don’t want to not be a musician.” We had a little bit of a lineup change there in order to start touring. Those are the things I associate with I Don’t Want to Grow Up.

The album was also your first time working as a record producer. Can you share the story of how that role came about?

I was maybe the pro tem producer. What I mean by that is, the engineer at the time, David Tarling, literally the day we started the record received some very bad news about his long-term health. He never told us what it was, but he was getting really loaded at the sessions. He would drink on the way up to the studio. There were these weird evening sessions—we’d get a discounted rate if we came in late at night and worked into the wee hours, so he was nodding off during the recording. I was interested in engineering, just because if you’re a nerdy math guy, it is intriguing. So at one point when he passed out, I just wheeled his chair off to the side and wheeled my chair in, and then there you go—I’m an engineer, even though I had no idea what I was doing. None whatsoever.

The band’s first four albums were released at a time when the music industry was corporate and glossy and full of drum machines and synthesizers. Was it difficult for the band to find an audience in those early years?

It has always been difficult. Case in point: do you remember that movie Decline of the Western Civilization? They were filming a lot of that at our practice room at the church. We shared a practice room with Black Flag. Literally, if any of us were just there and they’re shooting, Penelope [Spheeris, director] would go, “Hey, Bill? Frank? You’re in the shot. Can you [move]?” We did not look punk rock. We didn’t look the part; we didn’t act the part. We were the band that would get on these weird shows. I always joke there was the secret club of bands that couldn’t get on other shows. I think the impetus for what started the South Bay scene, and what started the glorious reign of SST Records and Black Flag and all that, is we didn’t have anywhere else. The Hollywood clubs didn’t want us, so [it would] be like us and the Suburban Lawns and Rhino 39 playing in Carson or the City of Industry.

It got easier once Milo Goes to College came out [in 1982]. It got a lot of good reviews, and all of a sudden, doors were opening instead of closing. And also, maybe, because I had come back into Descendents after my three-year tenure in Black Flag, some doors were opening for me personally to get us on shows and things like that. I was a little more savvy from that experience. I mean, God, it was really hard for a long time. It didn’t really get to be easy easy til we didn’t play for 10 years, and then we got back together and did Everything Sucks [in 1996]. Then things started to get easier for us. I guess we created a demand by providing scarcity.

Now, in addition to the Descendents you’re in the band ALL, which is an offshoot of the Descendents. Can you explain the difference between the two? Are you making new music with either of them?

Descendents have a whole bunch of new stuff recorded, so sometime soon, we’ll have a record. The difference between ALL [and Descendents]? Not much. It’s the three of us but with a different singer. Two bands couldn’t be more similar. But with ALL it was like starting over. Not much of the goodwill value of the Descendents name translated to ALL, so it was like starting over, in a way. But eventually we started playing decent shows to where a guy could afford to get a hamburger, but not enough to feed kids.

As you mentioned, you played a bunch of shows in 2024 and have done some live performances recently. Is touring still as much fun as it used to be?

For me, it’s more fun. One thing is the travel conditions are so much more favorable now than they were back then. Back then, if you were lucky, it was a van. You had the gear in a trailer behind the van, so you could outfit the van in some crude manner to where a few people could sleep while a couple other people were sitting up front driving. We never got hotels. It was either sleep in the van or find somebody to stay with after the show. And that was just forever and ever and ever.

At a certain point we got to where we could start using better vehicles, like a tour bus or something, where you actually have a place to sleep. That’s really what it comes down to is sleep. All of those early tours were just a big slog of sleep deprivation to where the days bleed together. And I’m not complaining about it, because the truth is, I wouldn’t trade those very hard touring conditions for anything in the world. But at the same time, I also wouldn’t want to go back to those at my age now. That might be a bit much.

I also enjoy it because I figured out how to have fun in front of people. I’ve always been a pretty self-conscious, insecure person, and also camera shy and all that. But in the last 5, 6 years, I’ve learned how to have fun doing it.

You are considered one of the best drummers out there; are there any drummers working today that you’re a fan of?

There’s like 100 drummers in 100 garages two miles from me right now in any direction that could play anything I play with one hand tied behind their back. It’s so crazy how good drummers have gotten. I guess part of it is maybe because you can look stuff up on YouTube, technique and all that. Everywhere I turn, there’s musicians that are just blowing my mind. Too many to count. It’s just everywhere. It’s kind of intimidating. [Laughs]

So many artists consider you to be an icon and a huge influence on their work. How is it for you when artists credit you as inspiring them to play or with influencing their sound?

Depending on the band, right? Some of them, you don’t want that blood on your hands. When the whole mall punk thing happened and we were being touted as one of the main progenitors, I thought, “Oh, really, no. I didn’t do it.” [Laughs]

I see it more as a sort of a continuum, because we certainly, Lord knows, had our influences, everything from the three I mentioned to the Buzzcocks, the band Generation X—Billy Idol’s band before he was Billy Idol, the Ramones, the Stooges, David Bowie’s band with Mick Ronson, the Kinks, the Animals, the Seeds, the Troggs. We had so many major influences. It’s like a river, and we’re just part of the river. We took some away from the river, and we added some to the river. And now we’re 60. If we influenced bands that are younger than us, well, that’s our job, right? Because we had bands that were older than us that influenced us.

Sometimes younger bands will influence us. When I started working with the band A Wilhelm Scream, they renewed my faith in rock. I just was so blown away by what they were doing. And when we started working with Zeke, I was like, “Whoa!” So bands could be younger than us, too, and still have an influence on us. Yeah, it’s flattering to think that we’ve left some kind of mark. It’s flattering.

In just a couple of years it’ll be the 50th anniversary of the Descendents. If you could go back to those early days and give yourself advice, what would you say?

Oh, wow! Nobody’s ever asked me that. [Long pause] You know, I can’t think of anything. I feel like we handled it the way I’d like us to handle it. Mind you, some of our lyrics when we were young were pretty atrocious, either really trite high school poetry or flat-out offensive things that kids say to each other to be mean. I probably wouldn’t do that stuff again, but that’s part of being a dumb kid with your head up your ass. You kind of have to do that, right? Don’t you have to make all those mistakes? That older Bill could prevent younger Bill from doing it, but that’s not how you get where you are in life. You have to fall on your face a bunch of times, right?

To learn more about Descendents, visit Instagram.

To purchase the reissue of I Don’t Want to Grow Up, click here.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You might also enjoy…