CR 075: Gris Grimly on Movies, Monsters, and Marrying Contemporary Art with Classic Texts

The acclaimed illustrator discusses his innovative artwork and his efforts to make literature accessible to young readers.

For more than 20 years, Gris Grimly’s playfully macabre images have attracted legions of loyal fans. He has illustrated picture books, produced and directed music videos and short films, exhibited his paintings in galleries, and most recently, illustrated tarot cards based on Elvira, Mistress of the Dark.

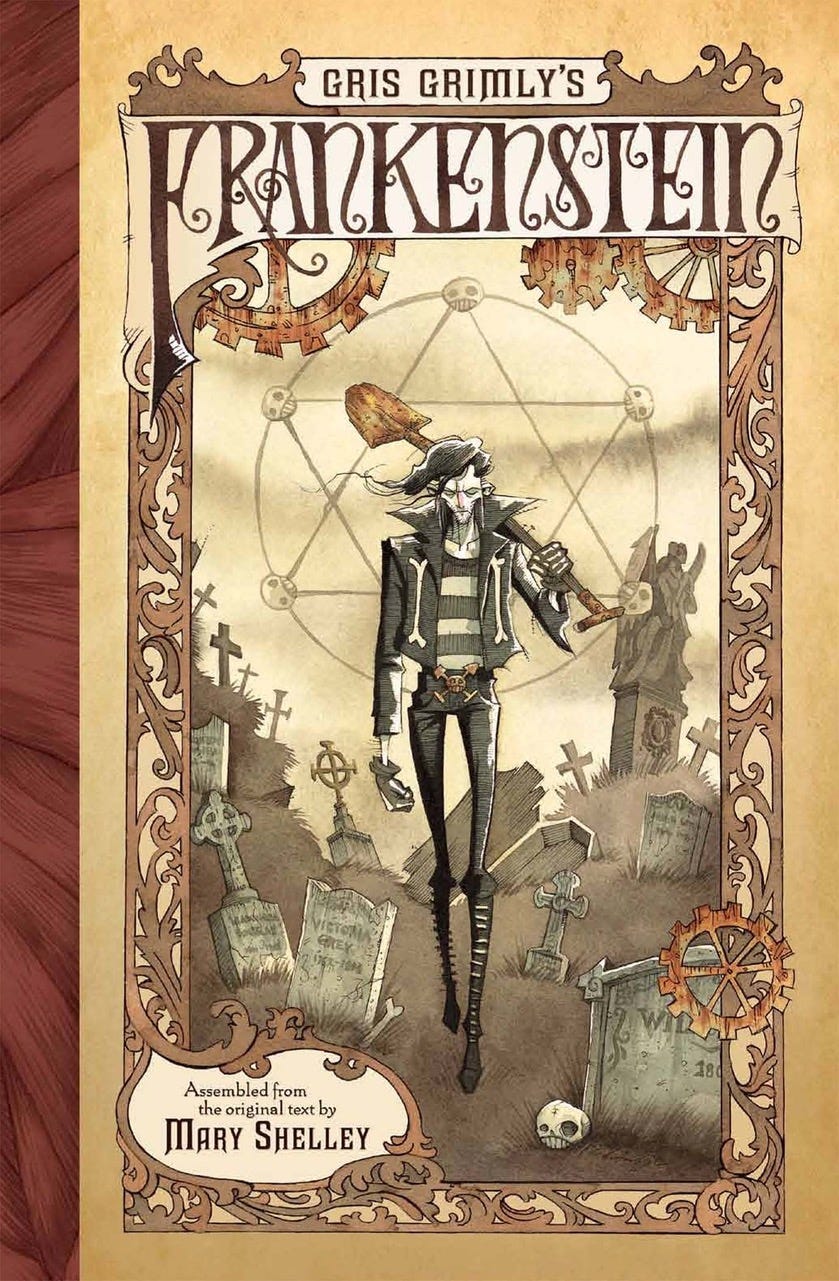

But it was his graphic adaptation of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein that he says changed the way he views his work. “This company approached me, wanting to make it into a curriculum for seventh and eighth grade students,” Grimly says. “I agreed to it, never realizing that this book that they use as part of their curriculum ended up getting circulated by the thousands across all these schools. All these seventh and eighth graders are now reading my version of Frankenstein, and those images are impacting them. I get letters from teachers all the time saying some of their students have difficulty reading these Victorian texts, and they know it’s my art that is allowing them to comprehend this literature, which just touches my heart. It gives me a purpose.”

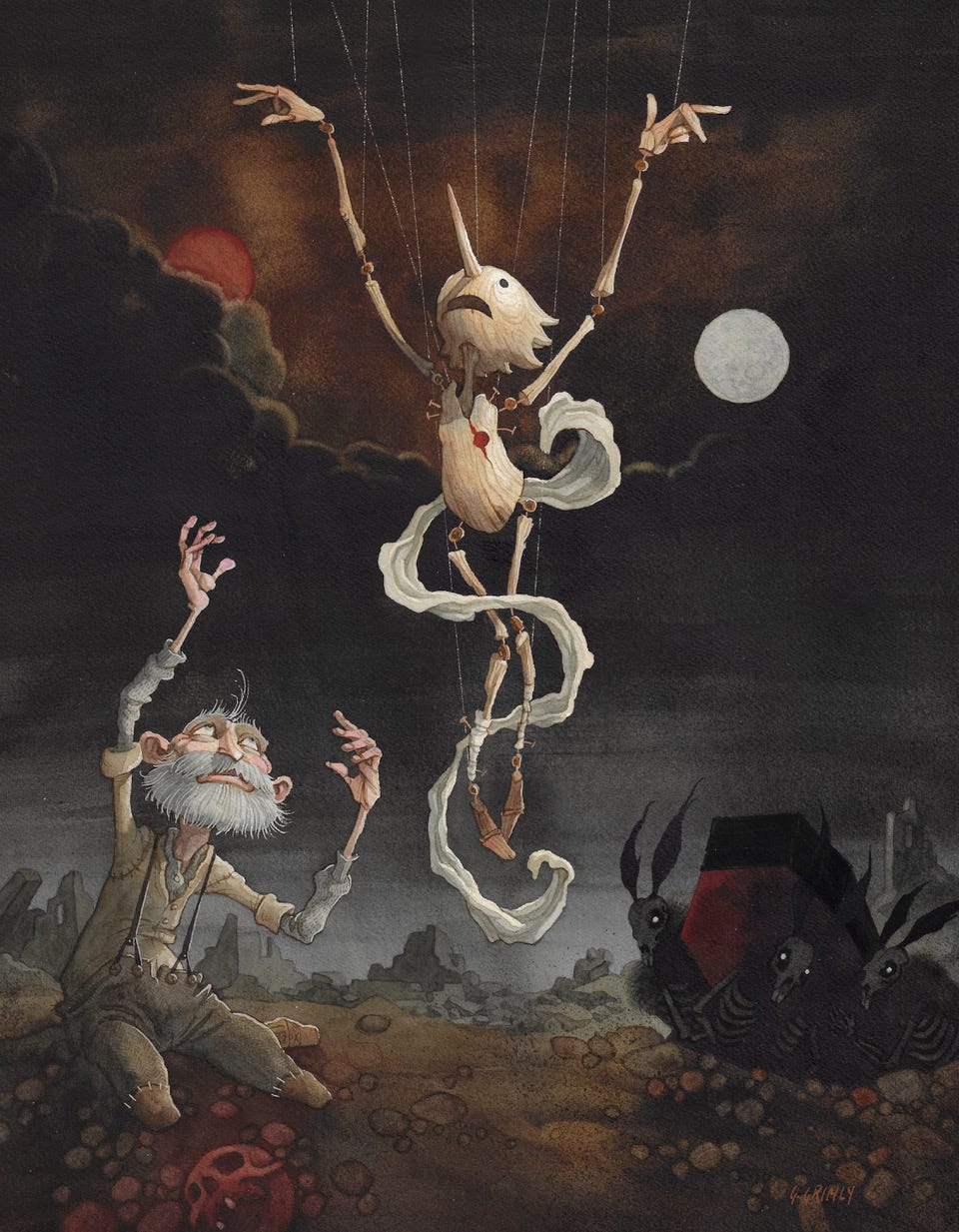

In addition to Frankenstein, Grimly has created visual interpretations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Madness, Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio, and Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. All stories, he says, that are important for kids to read. “A lot of these older stories deal with archetypes and symbols that I believe impact the spiritual growth of humanity as a collective—everything from Grimms’ Fairy Tales [to] a lot of the Victorian literature—and if we’re not telling those stories and people aren’t absorbing those stories, we’re losing a very important message for mankind. So the fact that I’ve illustrated Frankenstein and it’s been able to reach kids that normally would not read that literature makes me feel really good.”

I chatted with Grimly over Zoom about his upbringing, his fondness for monsters and outcasts, and how he came to work with Guillermo del Toro.

This content contains affiliate links. I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

SANDRA EBEJER: When did you first develop an interest in the arts? Were you raised in an arts-loving household?

GRIS GRIMLY: Not really, but I was born attracted to the arts. My mom started collecting material that I drew at the age of three and four. At that time period, I was mostly drawing wildlife. Primarily beavers, for some reason. I was really fascinated by beavers, so I drew beavers all the time. And she kept all those pictures that I drew, so I know I’ve been drawing since then.

I grew up on a farm—my dad’s a farmer and my mom was a housewife, so arts weren’t really part of our upbringing. I was born in rural Nebraska, so the culture here was very Midwest farmer, and the arts were not really present. I don’t know how I got into it, but I did, and I just always loved to draw. My parents did foster that. You see many situations, especially in a farm family, where the son is expected to carry on that legacy, and my dad realized that it wasn’t an interest of mine. Both my parents encouraged me to pursue the arts, so that’s what I did.

The first painting of yours that I recall seeing was Miss Muffet. I’m curious how you went from those early beaver drawings to the style you’re so widely known for.

When I was four-and-a-half, I got burned severely. I fell in a bucket of boiling water while my family was butchering chickens. For those that don’t know this kind of lifestyle, you have a big bucket of water that’s boiling, and you dip the chickens in, and it loosens up the feathers so you could pluck the feathers out. I was playing with my cousins, and somehow I fell backwards into one of these buckets of boiling water. I was sent to an emergency room and spent a month in the hospital getting skin grafts to heal the burn scars. Looking back, that’s when I noticed there was a shift in my interest in art, and I was more drawn to monsters and symbols of death. And that continued not just in what I drew, but also what I was fascinated by. That would be a springboard for when I became more interested in fantasy and used to draw things like chariots that were made out of bones. I was pretty young at this time. I remember my mom had concerns about it, not really understanding where this was coming from. But I see that as a major changing point in my interest.

One of the things you’ve become known for is doing graphic interpretations of well-known titles. When you are adapting pre-existing works, how do you pay homage to the original while still making it your own?

I would say that is one of the challenging things about touching a classic. I do respect the material that I’m approaching, but I also know that a lot of this material has been done over and over and if I can’t give it new breath, then what’s the point? This was something that I battled with for Frankenstein. Frankenstein was always a story that interested me. It could have something to do with me being burned and feeling deformed or like a monster and seeking acceptance from peers in society.

Frankenstein was always a story that I had aspirations to illustrate but never did. Bernie Wrightson did a version of Frankenstein that I’m a huge fan of. And when you do something like that, you want to compare yourself to the other people who have done it and say, “I can never achieve this. And even if I did achieve this, I would be copying this.” It wasn’t until I came to an idea of how I could make it my own and make it so different that it could reach a different audience [that I attempted it]. I created this kind of punk rock, fantasy Frankenstein. It’s not historical, it’s not Victorian, but it has Victorian elements to it. I was just having fun with it.

Is it intimidating to take on a project like Frankenstein that already has a large fan base?

Yeah, here’s the thing: you’re not going to please everyone no matter what you do. There’s going to be haters and someone’s not going to be happy with what you do, so you have to just do what makes you happy. It will find its audience and those that want to hate on it can hate on it, and it is what it is.

How did you come to work on the Pinocchio film with Guillermo del Toro?

That is a long story that I love to tell because, to me, it proves that magic exists in this world, and that there are forces that are pulling strings beyond our comprehension and beyond our own capabilities of perception. So, [my illustrated] Pinocchio had just been released as a book. This is 2003. I was working with another artist who was creating a sculpture out of my Pinocchio characters. This was a side project for him. I had just started in my career, but seeing these little three-dimensional versions of Pinocchio made me realize how great this would be as a stop-motion film, and I started to make a list of directors that I would approach to make this happen. Guillermo was top on the list for many reasons. I’m a fan of his work. I knew that in interviews he’s mentioned how he loves puppets and he loves stop-motion, so he seemed like the ideal candidate to direct Pinocchio.

I started working on little sketches of how this would translate into a movie. At the same time, my artwork for Pinocchio was being exhibited at Van Eaton Galleries in Sherman Oaks, and I get a call from the curator there. He says, “You’ll never believe this, but Guillermo del Toro just came in and bought a piece of your Pinocchio art.” I said, “Are you kidding? Can you get me a meeting with him?” He wrangled up a meeting, and before you knew it, I was sitting in a restaurant having lunch with Guillermo. I had my little envelope of sketches with me, and he sat there and ate shrimp, and I pitched him a concept of Pinocchio. I finished and there was a silence as he finishes chewing and wipes his mouth with his napkin. I asked him, “Will you direct this?” And he says, “No.” [Laughs] He goes, “I think you should. I will produce it.” He saw that I had a vision for this, and he wanted to help me bring that into a realization.

Creative Reverberations is a reader-supported publication. Each interview takes many hours of work. To receive new posts and support my work, please subscribe.

Shortly after that, I got a call from the Jim Henson Company because my manager [at the time] got a job in development at Jim Henson. He calls me into his office, holds up my copy of Pinocchio, and says, “Have you ever thought about making a movie out of this?” I said, “I just met with Guillermo, and he’s interested in making this with me.” And he said, “That’s great. We would love to work with Guillermo.” And all of a sudden, these pieces started to come together.

At that time it was still pre-development, me working out of my own apartment, going in for meetings every once in a while. We brought in a writer that worked on it. There was a co-director that was working on it with me, but nothing really big and substantial, because the funds weren’t there. And then in 2009, this French company Pathé invested development funds into the project. We got office space on the Jim Henson lot, and Guillermo would come in maybe once a week and meet with us. We worked on it for about a month and brought in maybe five artists. We hired a writer and started to develop this pitch for Pinocchio. And in 2010 we started to pitch it to all the major studios. They all ended up passing.

I was having a conversation with Guillermo, and I said, “What now?” And he said, “Well, we could either shelve it and no one ever sees this, or I can see if I can get it made as the director.” And so that was the decision we made. This is 2011, and years went by and it seemed like it just wasn’t going to happen. And then I got word around 2018 that it sold, and Netflix was picking it up. From then, Guillermo and his team shot like a bullet and created an amazing adaptation of what we had started. It’s something I’m very proud of.

That’s incredible. There are some obvious influences on your work—horror films, classic literature—but are there any influences that people might be surprised by?

Well, Mercer Mayer is an influence. I think he’s a subconscious influence. I mean, I should have realized because I loved his books growing up. There was a book called Liza Lou and the Yeller Belly Swamp, which I loved as a kid. Those images burned into my memory. But I was doing a signing probably 10 years ago and someone asked me, “I see a lot of similarities in your work and Mercer Mayer’s. Is he an influence?” And I said, “I didn’t know he was, but you’re probably right.” And now that I look at it, there’s a few things that I definitely think transitioned over from his work. I would [also] have to say [illustrator] Brian Froud, not because I was looking at Brian Froud’s art or had any books on Brian Froud or even knew who Brian Froud was, but I was obsessed with The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth, so his character designs in those films were a big influence on me.

I think the obvious one is Tim Burton. Everyone mentions that. I went to go see Batman because I liked Batman, and I went to see Beetlejuice because it looked cool, and I went to see Edward Scissorhands because it looked cool. I wasn’t realizing that they were made from the same director. I was just like, “I love this movie!” I remember when The Nightmare Before Christmas came out and how that affected me. You’d just never seen anything like that before. You could be a teenager and go see a cartoon like that in the theater and not have shame. There was nothing else like that in the theaters. If it was a cartoon, it was a Disney cartoon and it was cute and it was happy, and that movie comes out and it was just incredible. I would say the Rankin/Bass films, like The Hobbit and The Last Unicorn and The Flight of the Dragons, all have the same style. Those films were a big influence on me.

Do you draw or paint every day?

No. There was a period in my life when I used to all the time. Sometimes I’ll spend a long period just writing stories and then I miss it. And if weeks go by, sometimes you feel like your art muscles are stiff and you gotta get back into it. A lot of these films I’m a producer on and there might be teams of artists that are working on it. They bring ideas to the table, and my job is more to look at it, and [there are] a lot of meetings and writing concepts and ideas, so I’m not just doing art.

Is there anything you struggle with as an artist? Anything you’d like to get better at?

My art. All of it. I mean, there’s incredible talent out there, and I can’t help but look at other artists and be inspired—which is good, because it helps you push your limits. A lot of these kids, they’re coming out of high school doing work better than I’m doing now. You see some of this work and it’s inspiring.

I imagine you get asked to do a lot of various projects. You’ve designed wine bottle labels, you’ve illustrated books, you’ve worked on films and music videos. How do you decide which projects to take on? What does it have to have in order for you to say yes to it?

It depends on my schedule. If I don’t have much on my plate, I’ll take on stuff. If my plate is full and I know I’m picking up something that I’m going to be working on when I should be sleeping, it’s got to grab me and have an emotional draw. Lately, who I am as an artist and a creator is different than what I used to be. Now I really want to be putting things out in the world that helps shape humanity. I think no matter what you do, you have an effect. But I think in my early years, I just wanted to shock people. I saw work that was dark, for example, The Nightmare Before Christmas, and I saw that as, how dark can we push things for children? And that became my mindset when I started my career—how dark can I make things and they still get by as children’s books?

I wanted to be a comic book illustrator in the beginning, and that job just never came to me or the opportunities never happened. The first job that came to me was a book with Hyperion, which is owned by Disney, and it was a children’s book. Basically [they asked], “Can you do children’s books?” And I’m like, “I’ll figure it out. I’m training to work in comic books, and I’ll just take what I know and make it for kids.” I wasn’t passionate about children’s books, like some people are; I was passionate about creating horror stories and comic books. So I just used that as a pipeline to create children’s books. That idea in the back of my head was, how dark can I make this? I was making children’s books for adults that love children’s books, as opposed to making children’s books for children.

What I want to be creating now is stuff that really affects humanity in a positive way, even if it’s a dark story. I mean, fairy tales can be dark, but there’s a didactic component to it that, like I was saying earlier, helped shape civilization, and those stories are very important to be told as they are. I read a quote by Tolkien that was saying something about Disney when he created Snow White as a film, and how that adaptation lost so many important messages that were in the original fairy tale. I see that now, looking at these old fairy tales. These are important tales that mankind needs to know in order to become a conscious collective.

To learn more about Gris Grimly, visit his website.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You might also enjoy…