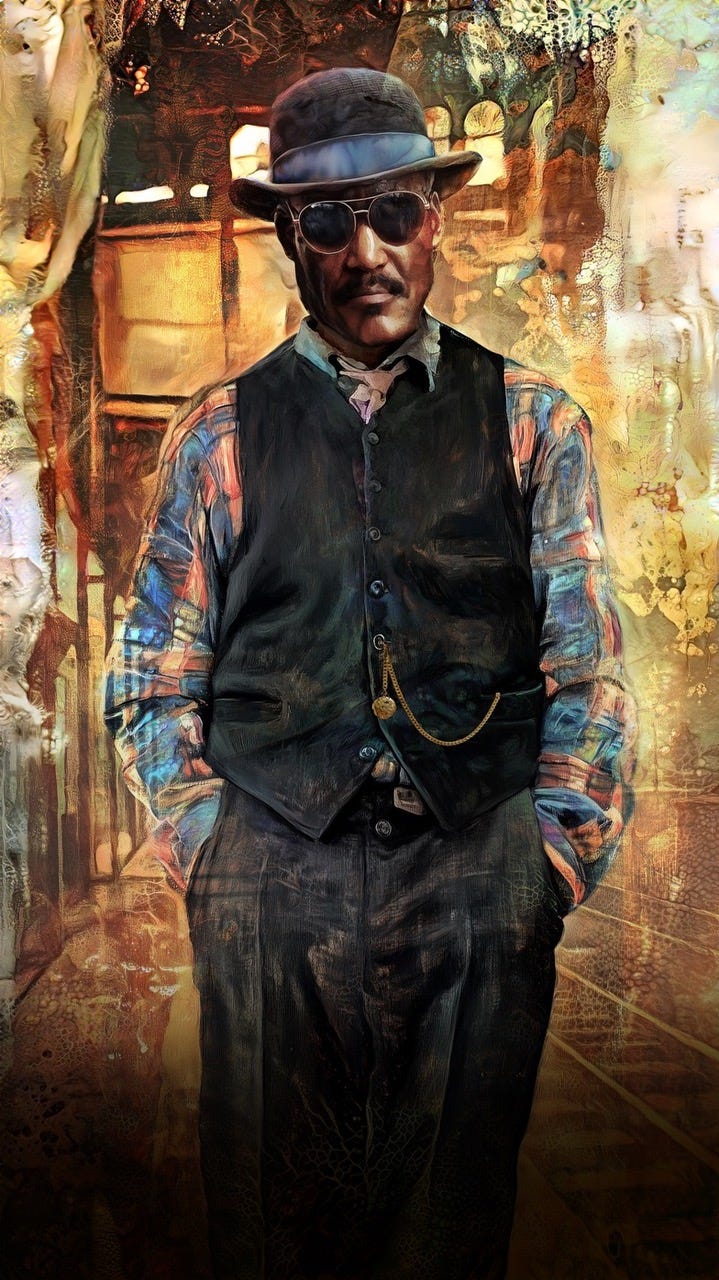

CR 081: Ruth E. Carter on Working with Spike, Presenting to Spielberg, and Costuming ‘Sinners’

The Oscar winning costume designer discusses her astounding career and her record-breaking Oscar nomination for “Sinners.”

In the 1980s, Ruth E. Carter was working toward a career in theatrical costume design when a friend introduced her to an up-and-coming filmmaker by the name of Spike Lee. The two hit it off, and Lee convinced Carter to design the costumes for his second feature, School Daze. Fast forward 38 years, and Carter is now one of the most sought-after costume designers working today. With more than 70 credits to her name, she has contributed her talents to a mind-blowing array of projects, including Do the Right Thing, Malcom X, Amistad, Selma, and How Stella Got Her Groove Back. An exhibit of her work, “Afrofuturism in Costume Design,” is currently on display at the African American Museum in Philadelphia, and a collection of her stories and sketches was published as a gorgeous coffee table book, The Art of Ruth E. Carter, in 2023.

Most notably, she is a trailblazer. In addition to being the first Black costume designer to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, in 2019 Carter became the first Black person to win an Oscar for costume design (for her work on Black Panther). In 2022, she made history yet again when she won an Oscar for Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, becoming the first Black woman to win two Academy Awards. And just a few weeks ago, she earned her fifth Oscar nomination—for her work on Ryan Coogler’s Sinners—becoming the most nominated Black woman in Oscar history. This most recent achievement, she says, was a complete shock.

“I wasn’t expecting that at all,” Carter says. “When that popped up on my feed, I had to stop and think, how long have I been doing this? This is the only job I’ve ever had. I take that back! I drove an ice cream truck in college. [Laughs] But I was doing this when I was in school, and right after school I started internships, and right after internships, I met Spike, and so my career started right away. I was nominated in ’93 when I was 32 years old [for Malcolm X]. So there’s a lifetime of dedication to this craft. And I’ve given so much to this industry that I’m honored that the recognition is there. There’s so many artists who don’t realize the impact they’ve had to their discipline until after they’re long gone. So I’m honored to be standing here today and being given the flowers of, ‘Thank you. You’ve been a pivotal role in bringing culture to the big screen.’”

Over Zoom, I spoke with Carter about her influences, her early days with Spike Lee, and what she thought when she first read the Sinners script.

This content contains affiliate links. I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

SANDRA EBEJER: When did you first develop a love for costume design? Were you interested in this as a child?

RUTH CARTER: Not as a child. Two of my brothers are visual artists. I had five brothers, and Robert was the middle boy, 10 years older than me. He studied art and went to art school, but he didn’t pursue it as a profession. He did have exhibitions as a kid. I remember going to our local movie theater and my brother’s art was on the walls being exhibited. We revered my brother Robert as the artist in the family. And my other brother, Roy, who was closest in age to me—we would play with art, we would draw, we would sketch. But Robert was like the supreme artist of the family, and that’s the thing that spurred me on to get into the visual arts.

I found a sewing machine, and I taught myself how to sew on it. It wasn’t to make clothes for myself; it was to be creative. And as I moved further along into college, I started out as a special ed major and wanted to work with special needs children. But that desire to be in the arts kept burning inside, and I eventually changed my major to theater arts. I didn’t know that it would be costume design. I was acting in plays, and there was a play I didn’t make the audition for, but the professor—in college, your professors are the directors—asked me if I wanted to do the costumes. And what I discovered was that I could play all the roles, not just one, by being a costume designer.

At Hampton University, where I went to school, they didn’t have a specialization in costume design. So I had to go to the library to read up on what exactly a costume designer is responsible for. It said sketching. And I was like, “I do that!” And it said sewing. And I was like, “I know how to do that!” And eventually that was the thing that defined me at Hampton. I was known all over campus as the costume designer. I did the plays, I did musicals. I was very busy on campus my last two years of school as a costume designer. It kind of found me.

You began working with Spike Lee pretty early on in both of your careers. I read an interview where you said, “I think I taught Spike and Spike taught me.” When you look back on those early days of your careers, what comes to mind? What would you say you learned from one another?

We both had a passion for telling African American stories. We also learned from each other the field of filmmaking. Every year, we went back to 40 Acres [production company] to learn and to create another film. So we would always discuss the film we did the year prior and talk about what we could do differently. We went to see what we call the dailies, or the rushes, every night. After we filmed during the day, we’d go to the theater and we would watch what we shot the day before, so we could correct some of the things that we felt were a little off. That was a learning lab for all of us. And that was the biggest takeaway with Spike emerging as a young filmmaker, and all of us along the journey with him. He was our leader, because he’d graduated from film school and he had another perspective to offer some of us who had come out of theater. He really wanted to teach us the medium of film. And also, we wanted to show representation. We wanted to show ourselves in front of the cameras the way we saw ourselves in everyday life. There was so much story and so much purpose in what we started together.

There are some directors—Spike Lee, Ryan Coogler, John Singleton, Robert Townsend—whom you’ve worked with multiple times. But you’ve also worked with some directors, like Steven Spielberg and Ava DuVernay, only once. Do you find that it’s easier to enter a project when you already have a strong relationship with the director? When you haven’t worked with someone before, is there an adjustment period?

Well, yes, there is an adjustment period anytime you work together with someone new. But Spike Lee is unique. Every story that he tells has a unique formula to it. Malcolm X was so different from Mo’ Better Blues. Mo’ Better Blues was so different from Do the Right Thing. So when you work with someone like Spike, who’s very clear about the direction of the art, you really are absorbing and seeking knowledge and asking questions and immersing in this new idea, the same way you would with a new director and a new script.

They all want you [to present]. I remember doing a big presentation for Steven Spielberg. I did a big presentation for Ava DuVernay. I always do a big presentation for Spike Lee, and then I get notes. So I think that the process is mine. My process for creating costumes remains constant, and they want to see what my process is. Sometimes it’s not a big presentation, it’s just a small postcard. I remember being out in the middle of the Long Island Sound on a boat, and Steven [Spielberg] asked to see how the character Cinqué in Amistad was going to look on the boat of his return to Africa. We were out in the water. I was away from my normal truck, where I have all of my research and everything right at my disposal, and probably a presentation that I could have offered, but all I had with me at that moment was a postcard that was a painting of Cinqué in a white cross-body drape, which looked like he was on a ship. So I walked over to him with the postcard, and he breathed in and held his chest because it felt so authentic and real to the story.

So, as you develop your relationships with directors, you find ways that resonate with them all individually, but that process that you need as an artist to go through getting costumes developed remains constant. I find that the best way to work with each one or to absorb their differences is to be a good listener. Really listen to where they want to go with the story, visually with costumes, what resonates with them, what they find fascinating. When you hear all of those little things, you can expound on it.

Creative Reverberations is a reader-supported publication. Each interview takes many hours of work. To receive new posts and support my work, please subscribe.

Who are your influences? Are there any artists you turn to when you’re seeking inspiration?

Oh God, yes! There’s so many. I keep going back to Romare Bearden. It’s the idea of collaging that I feel costumes do in film. It’s a collage of textures, of characters, of colors, and he’s always been a huge influence in my art. Or if I want to be inspired, I can open up Romare Bearden and find it. I’m also inspired by photographers—James Van Der Zee, Teenie Harris—because it’s truth, it’s honesty. It’s a picture. It’s right there playing out in front of you. I loved Weegee. I love looking at Depression-era photography, just because there’s so much character in the faces. There’s no posing. It’s so rich and raw. I could go on and on.

When I did Amistad, I was really looking at the Neoclassics and trying to get color palettes from [Eugène] Delacroix and [Jacques-Louis] David. I love using art in that way to inspire, to get a mood. If there’s a mood I’m looking for, I always find it in the visual arts. And if there’s reality [I need to reference], there’s so many beautiful compilations of books, like Gordon Parks, that have displayed different eras of time. I even look at Ebony magazines from the 1950s and ’60s. I have a collection of those, and those little Jet magazines. There’s no place that’s sacred. I go everywhere.

You recently received an Oscar nomination for your work on Sinners, making you the most nominated Black woman in Oscar history. Sinners is such an extraordinary film across the board—the writing, the directing, the acting, the costumes, the music. It’s also an incredibly inventive way to present a story about white supremacy and racism. What were your thoughts when you first saw the script for the movie?

I’ve always loved historical dramas. I’ve loved doing them. I’ve been studying Black history along the way with every job—Rosewood, Malcolm X, Selma—so when I got the script, I was astounded that Ryan Coogler was going to do a period piece in his next film after the two Black Panther films. I just did not see that coming. I was thrilled and excited, because this is every reason why I ever wanted to be a costume designer—to recreate some of our history. And then when I read the vampire part, I was like, “Wait, what is this?” [Laughs] I had to get used to it, that it was actually metaphoric, and go back through the script again and understand the story that we were telling.

I really did focus on being as authentic as I could. That’s always been a part of my ideal. Because I feel like I’m a conduit. I’m a person who gives history where we don’t get it in school. I teach in that way. So I really wanted the sharecropper experience, the layers of Smoke and Stack coming down from Chicago, the Annie and her voodoo ways, Mary returning to Mississippi, and what that meant for people who were migrating and sharecropping in the South. I really did need that to feel real for me. Then the vampire stuff was just something added. [Laughs] I let my team address the needs of what vampiring would require, which is multiples and lots of blood on clothes.

Your two Oscar wins were for Black Panther and Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. The Black Panther character has existed in the Marvel universe since the 1960s. Does your approach to a film change when you’re working on something that is based on existing IP, especially for a company like Marvel?

I thought it would when I first got those projects. I thought it would change the way that I worked, because there’s already so much there. There’s already a machine at Marvel that’s creating illustrations, that has so much input in how their IP is displayed in film. But what I realized was that they hired me, and there was a reason why they hired me, and that is for world building. Ryan Coogler said he was a kid on his dad’s lap watching Malcolm X and he was really excited to have me come in. So that told me that I had a role in the story of making the Black Panther films, not only the world building of Wakanda, but also that added touch that would make the Black Panther costume really become a part of the history of Black culture. And he was developed in the ’60s by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. They wanted to be a part of civil rights. They wanted to ingest something into the time that would be inspiring for people who were into the comics. And so they created Black Panther. And I was able to take their image of the Black Panther and layer on top of it, like the Okavango triangle and the striations of tribal markings, and how we view Chadwick Boseman as T’Challa around the Kingdom of Wakanda, how that looked. There was a real need for me to dive into Black culture once I was given the job.

Can you talk me through what it’s like to design costumes for a movie series like Black Panther? Because those were huge films with hundreds of actors, each needing their own costume that would reflect their individual character. Are you personally designing each costume? What’s the process like for films of that magnitude?

I usually have about six illustrators. We have weekly meetings where we discuss research. If they’re with me in the room, like it was on the first Black Panther, they have boards in front of their computers. They’re working from posted notes that I have all around on different artifacts and curated imagery from African art, or wherever it comes from, and they’re combining all of these ideas. There’s also a period of time where, once the actor is cast, one by one, individual by individual, step by step, we are trying things. We are trying on chest plates. We’re trying on colors. We’re putting together different shapes that work with their individual body types.

Sometimes it’s an illustration that we go straight into, and the armor is what it is. It’s an army of border tribe or king’s guardsmen, and it really doesn’t change. But there are also lots of other scenes where they have to be in their daily life and we have to keep it consistent, and we have to work with how the actor is going to actually portray the character. So we step into it, just step by step, and before you know it, we have a shape and then from the shape we have a color palette and a form. And I have a team of 20 people that are working behind the scenes—cutters, ager/dyers, assistants, shoppers, all kinds of people that go into creating them one by one.

How much, if at all, do the actors weigh in on their costumes?

I don’t think that the actors want to be costume designers, but they do have to wear a costume in front of the camera. They’re in front of the camera, not me. So it’s really important that they actually feel good. So as we research and try things on, shoes become very important, undergarments become very important. Colors—like if the shade of green isn’t their best shade of green, we make those adjustments. On Marvel films, though, we have had so many meetings prior to that person coming in, there’s a real tight area of movement. Like I can’t change the way the Dora looks from one costume to the next. It’s pretty consistent. But on a lot of my other films, I ask questions in the fittings. I ask, “What are you doing there? How are you going to portray this character? What’s your daily life? How have you immersed yourself into this character? What do they eat for breakfast?” All those things help you see the character that they want to play, and it makes it a lot easier for you to discover something that they enjoy. When you can bring them an article of clothing that feels like the narrative that they have created for themselves, they really enjoy that.

In looking over your IMDb credits, you’ve worked on a mind-blowing number of films that celebrate Black history and culture.

Only job I ever had! [Laughs]

When you think back on your career so far, are there any projects or moments that stand out?

Oh yeah. They’re like my kids, and the ones that don’t get much recognition are the ones that I sometimes have had the most fun on. I did one called Sparkle, and it was [about] girl singing groups in the ’60s. I really enjoyed the cast. I enjoyed creating the costumes. We discovered Paco Rabanne and Rudi Gernreich, recreated some of the big fashion designers of the ’60s, and created some pretty amazing costumes. The movie itself didn’t do that well, but the costumes I enjoyed so much.

What do you want your legacy to be?

I would like my legacy to be that costume design is an art form, that it’s a part of the filmmaking process that is a serious profession that deserves respect and to be studied. And that when you are someone like me, and you can examine culture—Black culture, Korean culture, whatever the culture is—that you can really make a statement with what you do with costumes.

To learn more about Ruth E. Carter, visit her website.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You might also enjoy…